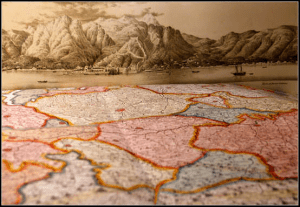

Map and Territory: Navigating Language

March 22, 2011 11 Comments

Three philosophy grad students were stranded on an abandoned island. They started wandering around exploring, making a map of the territory. To make it easier to talk about, they labeled the northern part of the island “Section A” and the southern part “Section B”, writing it in big letters on the top and bottom of the map.

Three philosophy grad students were stranded on an abandoned island. They started wandering around exploring, making a map of the territory. To make it easier to talk about, they labeled the northern part of the island “Section A” and the southern part “Section B”, writing it in big letters on the top and bottom of the map.

After exploring a bit, Chris called out excitedly. “I found a radio in Section A! Check it out, we’re saved!” His friends came running.

“This is in Section B, not Section A,” said Bruce. “It’s south of the tree line, which is the obvious division between north and south.”

“Of course it’s Section A,” replied Alice. “This is north of the river, which is the way to divide the island.”

Chris shrugged. “I guess we never decided exactly what the border was; I just assumed we were using the river. It’s not like the radio moves based on what section we call this. We agree that it’s north of the river and south of the trees. It’s Section A if we use the river, Section B if we use the forest. Let’s just decide to use one or the other. Neither way is ‘right’ or ‘wrong’; we’re making them up.”

Alice and Bruce weren’t buying it.

“What do you mean, we’re just making it up? The forest is real and the river is real. One of them makes the real boundary between Section A and Section B!”

Chris sat down to use the radio to call for help, leaving his two friends to their bickering.

Alice and Bruce were experiencing the “map and territory” confusion. A map is a mind-made categorization of real things in the territory. It doesn’t make sense to say that the decision to divide the territory in one way or another is “right” or “wrong”, only more or less useful in different contexts.

This comes up all too often in language. Like sections on a map, words are societal tools we use to categorize and communicate the real things we experience. Our society has some well-defined words like ‘hydrogen’ – we have a good shared understanding of exactly which conditions must be met to determine whether or not we should call something ‘hydrogen’.

But the boundaries around other words are hazier. People argue over whether to call something ‘love’, whether to call it ‘art’, and (one of the most contentious) whether to call it ‘moral’. By some definitions, a urinal on a pedestal qualifies as art, by other definitions it doesn’t. Society hasn’t agreed upon clear-cut boundaries for which feelings, objects, or actions fit into those categories. But the arguments are not about reality itself – they’re over the labels, the language map.

In many philosophical discussions, the distinction is muddied or lost. When the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy gives an Analysis of Knowledge and examines whether or not a person “knows” something, they’re really at the ‘map’ level, discussing which facts, principles, and phenomena we choose to group under the label ‘knowledge’.

One such argument is over whether a person can know something without believing it to be true. Philosopher Colin Radford said yes, giving the example of a hypothetical student named Albert who thought he was guessing on a test but actually remembered correctly. Other philosophers such as “Evidentialists” have disagreed, and claimed that it wasn’t knowledge after all because it lacked proper justification. But their argument is like the grad students arguing over whether the radio is in Section A. Nothing about Albert’s confidence level, correctness, or justification for his guess changes based on whether or not it’s labeled “knowledge”.

The best way I’ve found to clear up the confusion is to change the sentence’s subject. Instead of “What is moral?” ask “What things do people call moral?” Instead of “What is it to be a law of nature?” ask “What things do people call laws of nature?” Or, if you want to be meticulous, phrase your question “What conditions must be met for us to call a thing moral?” The new wording highlights the distinction between the label and the things themselves.

It’s important to have words that categorize the world well so we can talk about a concept accurately and clearly. But an argument over the map isn’t an argument about the underlying reality.

Is this what people call a blog post?

Seriously.. yeah problems of pure semantics over a term can only be answered by reference to another term that happens not to be contested. We may disagree that an object is art but we’d like agree that art is something that necessarily includes “an artifact or display produced with the intent of conveying or eliciting a feeling or idea”.

The distinction between the label and the thing being labelled is relevant does exist.

What is mind-blowing is that we use a common language, English or whatever, as if it was really commonly grounded into each of our minds. But of course what everybody can commonly agree is not “the things being labelled” , but the labels (i.e. words)

The reason being we don’t have the technical means to open the brain and see which node each label point to.

This problem does not exist within computers where every instruction and language token has an absolutely non-ambiguous mean embedded into their core.

By hacking the code-source of the brain (Church Turing hypothesis), we ll shatter language ambiguity and begin our merge with machines.

Interesting to look at is the lojban language, an attempt to create an ambiguous natural language that can be parsable by machines.( en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lojban)

This is how I feel about words like “ironic.” I’ve seen so many people correct others on bad usage of that word, despite the fact that their use of the word correctly conveyed how they felt on the subject. So if you understand the meaning, why does the definition matter?

It’s curious because your first example of hydrogen has a very different kind of delineation in regard to what is map and what is territory than your latter example of, say, morality does. The shift is not just one of agreed boundaries of what defines the object, but also that the very ambiguity of what is art or morality as object means that there is a much less clear separation between map and territory. That is to say that if the map changes, so does the territory – which is a very divergent idea to the example of the radio.

Edward Clint:

Is this what people call a blog comment? Srsly, you appear to have missed the point quite ironically – the semantics are map, the territory is understanding that the words being used are representative of a real territory (not just another ‘agreed upon’ term).

Just to point out the obvious: the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy doesn’t give an analysis of knowledge. It hosts a brief literature review on the topic, written by Matthias Steup. Attributing views or accounts or analyses to the SEP is incorrect and misleading, and perhaps an indication of misunderstanding on the part of the attributer as to what the SEP is.

On another note, philosophers and linguists have been hip to the distinction you’ve stumbled upon here for a long, long time. Pleading for folks to be sensitive to the distinction between labels and the labelled is just pleading for them to be sensitive to the use/mention distinction and (one some conceptions) the distinction between semantics and metaphysics. These distinctions are already present in these discussions, whether or not you yourself have missed them. When questions are about the terrain, we consider the terrain; when about the map, we consider the map, and when about the relation between the two (which, despite the impressively crude picture you’ve presented here, is an incredibly complicated issue), we talk about that relation. Careful and charitable reading of contemporary work would make that obvious. If a reader doesn’t pick up on it, that says something about the reader.

But I guess that asking someone to put in the time to actually learn something about a field before launching criticisms at it is asking a bit too much? Then again, remaining willfully ignorant of publicly available information so that one may continue to strawman their opponent is a pretty powerful strategy. Look where it’s gotten the anti-evolution folks. Great company to be in, eh?

Hi Wesley.

The philosophers I’ve talked to have told me that the question ‘what is knowledge’ is an investigation into the nature of the world, not just a semantic decision about how we would like to define the word knowledge. That’s what I perceive to be the map-territory fallacy, or as you rightly pointed out, the use-mention fallacy. But I’d be very interested to read any materials you could recommend to me in which epistemologists acknowledge that the question ‘what is knowledge’ a semantic one; so far I haven’t found any. If it is true that they see this question as semantic, I am surprised that it has attracted so much time and effort.

I think some of the above commenters have missed the distinction between an interesting little blog post about an area of communications commonly misused in everyday discussion, and a scholarly philosophical critique. There is no need to criticize Jesse simply for bringing up a topic that may have been discussed elsewhere.

One of the useful aspects of blogs is their ability to communicate simplified forms of complex ideas to non-specialists.

Pingback: Funding for which arts? « Measure of Doubt

Mr Fossils,

I would normally agree with you. However, given additional contextual information (i.e. personal conversations with the author), I am extremely confident that this was not intended as a discussion of a common mistake in everyday discussion, but, indeed, as a scholarly critique. This claim is further corroborated by much of the post itself.

Julia,

I never meant to claim that endeavors into the nature of knowledge are entirely semantic. Questions about what knowledge is are, indeed, metaphysical questions. Semantics plays are very useful purpose, however, insofar as we can gather some insight by studying the semantics of epistemic discourse, such as felicitous uses of, say, the predicate ‘knows’ within the context of attributions that are accepted as true or inferences that are accepted as valid by competent speakers. By studying the semantic behavior of such a predicate, we can come to learn what sort of property it denotes, and further, what that property must be like in order to make as much sense as possible out of the discourse. A common story is that ‘knows’ denotes some polyadic relation, on some accounts between an agent and a bit of information (typically conceived of as a proposition), and on others among an agent, a bit of information, and something like an epistemic standard or something along those lines. Another is that, given the semantic behavior of ‘knows’ (and its relatives and cognates), the only way to make sense of epistemic discourse is to claim that the predicate denotes different relations across contexts. By clearing up the semantic issues, we can help settle the metaphysical questions, such as how many relations are in play and what it takes in order to stand in them. I said ‘help settle’, though. Not ‘settle’.

In short: the semantics of epistemic terms *informs* the study of epistemic concepts, properties, and relations. This is why, in the contemporary landscape, it’s hard to do much by way of interesting epistemology without at least some working knowledge of basic linguistics, or without a data set for what folks take to be felicitous and true (or otherwise) epistemic claims. Semantics informs, but does not in any way exhaust, the inquiry.

Actually Wes, after our conversations (but before I posted this) I looked over my draft to make sure I *wasn’t* making any sweeping generalizations about the entire field of epistemology or philosophy as a whole. I even made a couple wording changes to try to make that clearer for when this post went up.

In fact, it’s a pretty weak claim that “many philosophical discussions” muddy the distinction. I might make stronger claims later (especially when the metaphysical topics come up), but surely even you would agree with such a weak claim?

If your claim is merely that some philosophers are sloppy, unclear, or just bad at what they do, and that this unfortunate fact occasionally causes them to commit the philosophical cardinal sins of talking past each other or confusing the topic, then I can agree wholeheartedly.